...Or, "Why I Think Atonal Operas About Pederasty and Demonic Possession Are More Interesting Than Operas About Italian Peasants"

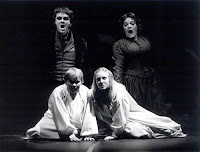

The Turn of the Screw was written by Benjamin Britten in the 1950s, based on the novella by Henry James of the same name. Superficially, it is a ghost story. A governess comes to an estate in Bly, a small village in England, to look after a little boy named Miles and a girl named Flora. After meeting the children, she learns from the housekeeper Mrs. Grose that their previous governess, Mrs. Jessel, and the groundskeeper, Peter Quint, both died in mysterious accidents after abusing the children. The story continues and the governess realizes that Jessel and Quint are slowly taking over Flora and Miles. The opera ends with the governess winning (losing?) the battle with Quint over Miles' soul, and he dies in her arms. Haunting, isn't it?

There are so many interesting aspects of this story and the music Britten composed to accompany it. It leaves so many things open-ended that it gives a lot of room for creative interpretation, and that is precisely what I hope to do. I will be taking the role of co-musical director of the production that Brown Opera Productions is doing, which gives me a lot of license as to how certain lines are sung or played and the way I want to pace the story. Ultimately, the director makes all creative decisions, but it is a collaborative effort. Hopefully, I will have lots of things to bring to the table.

This opera is haunting in so many ways. The questions I had to ask myself after I first listened through the music and saw a production of it were each in themselves questions that Britten and James scholars have struggled to answer since.

My first question: Why did Britten choose this story?

When composers have to decide what story they want to set, they are often making bold statements about their art, their personal lives, and the way they want to be portrayed. Mozart was advised not to set the Marriage of Figaro to an opera because it was an offensive story that poked fun at the aristocracy. The Magic Flute was his allegoric tribute to his Masonic brothers. Don Giovanni let him explore his guilt about his dead father.

Britten, like Mozart, was a prolific operatic composer: Albert Herring, Peter Grimes, Billy Budd, A Midsummer Night's Dream...just to name a few. Notice how most of them are about dudes.

I think it is somewhat unfair to highlight Britten's homosexuality as much as some authors have done. It's also easy to reduce Britten's choices of subject matter for his operas to him trying to find an outlet for homosexuality and his attraction to younger men.

Britten was an outsider. A homosexual in mid 20th-century Britain couldn't feel anything but that. He feels oppressed by his society. His operas become a way for him to channel that frustration, to explore the way in which him and the world he lives in is at odds.

Billy Budd, based on the slightly homo-erotic novella by Herman Melville, is about a beautiful young man who is ultimately condemned to death by a technicality in navy laws. Many smarter people will disagree with me, but I believe Britten saw a little bit of himself in Billy. Oppressed by the norms of society, yet forced to sing about how glorious it all is.

So how did feeling like an outsider inform his decision to set the James novella? I really don't know, but I have an idea. I am sure this idea will change as I listen to and watch the opera again and again. Still, I'm convinced that I've worked some of it out. Bear with me.

The Turn of the Screw is primarily about a governess fighting with a ghost of a man over the soul of a young boy.

Flora, Jessel, and Mrs. Grose are all really minor characters when you consider the attention Britten pays to the three.

I've come to the conclusion that the governess is supposed to represent Victorian society. She comes into the play, imposing order on the chaos that is the estate with no real owner. There is nothing much else to really indicate that she represents Victorian society, so my argument might already be dead here. But Quint, I think, is supposed to be Britten. Although the ghosts are supposed to be real, and have voices in the opera, I really think that they are to an extent, a figment of the governess' imagination, a projection of the evil she thinks she sees in the children. Of course they existed at one point, but the governess creates them after hearing about them and they grow into much more sinister forces in her head as the opera progresses. I remember hearing that Victorian England thought children inherently came with a bit of evil in them. Original sin and all that. So I think she sees Quint as something evil in the child that might grow to be something terrible. And this evil is the otherness of Quint and the sexuality he represents.

So the governess imagines a Quint growing inside Miles. Earlier in an expository song from Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper, it is revealed that Quint made "free" with everyone. Of course, this implies some sort of sexual relationship, but it can also mean that he disregarded the hierarchy within the household. As a groundskeeper, he was expected to steer clear of the old governess, Miss Jessel, because she was a lady.

So beyond sexual awakening, the governess is trying to tame this disobedience to the accepted order of things.

And although it may be irrelevant, I would like to come back to that idea I had about original sin. There is a terribly haunting song that Miles sings during his Latin lesson, which repeats the word "Malo" four times, giving a different definition each time. The most important definitions are probably "bad" and "apple," something I think Britten deliberately intended. The fall from innocence (another theme HEAVILY explored in this opera both musically and texturally) seems to be something the governess wants to prevent. (The Lesson-start from 1:27)

The final battle for Miles' soul is a battle between open expression and repression. Ultimately, it is too much for Miles and he dies. So, who is the murderer? Quint or the governess? Why and how he dies is still something of a mystery. I personally like the idea that she smothers him while trying to protect him from Quint.

I'm only trying to get a few of my ideas out there, so this is probably a superficial analysis. I'm not going to pretend I get Britten because I have a LOT more reading to do. Hopefully, I will come to understand more why Britten wrote this opera as I finish this Michael Kennedy biography.

I'll be trying to think through some of the other questions I have about the story. It's a really complex work. Another project I want to work on is to learn how to write about music and to write intelligently about it.

I recommend listening to the version with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, with Ian Bostridge playing Quint. There's a good version of it on youtube as well: 1982 Film Version

I find this version's prologue and implication of a sexual relationship between Quint, Jessel, and the children really uh...fascinating.

Happy listening!